Why the West Hates Russia

Russophobia has plagued the halls of Western power for 200 years — and it‘s only getting worse.

I have been both fascinated and exasperated at the level of Russophobia that is to be found in the “Collective West” these days. It seems that Russians are not only distrusted, but actively hated. Russian culture is being canceled; Russians themselves are being persecuted in many Western countries. Even young people are hopping on the anti-Russian bandwagon.

And of course Vladimir Putin is universally condemned as “Putler”, a malevolent mix of Hitler, Stalin, Peter the Great and any other odious dictator one can name.

To me, the word “Russophobia” is insufficient to describe this phenomenon: what most Westerners feel towards Russia and Russians is nothing less than a burning, fierce RACISM — an all-consuming hatred fuelled by the conviction that “Western values” are superior to “Russian values”, that Russian culture is crude and degenerate, and that Westerners themselves are morally and intellectually superior to the “mongol hordes” who inhabit Russia.

My anger and frustration over this suffocating anti-Russian atmosphere has prompted me to write articles attempting to explain how — and why — the West wants to annihilate Russia:

And yet, I still felt that I did not get the whole story. There must be more to it, I thought. This level of outright racism and hatred cannot just spring out of nowhere — it must have been brewing over a long period of time.

I decided to do some research from an historical perspective. What I found was at once baffling and frightening.

It all started with the British Empire

As with so many centres of misery in this world, the origins of Western Russophobia can be traced back to the British, who have been in a seemingly existential conflict with Russia since the early 1800's.

Indeed, for the British, the “Spy vs. Spy” war of espionage and covert actions centred in post-WWII Europe were just one skirmish in a global war that the British have been waging against Russia for generations.

Why Brits say Russia is “imperial” and “expansionist”

Britain’s hatred and distrust of Russia started when the British Empire was at its height, when the “sun never set” on their dominion, and London had fixed its hoary gaze on India and Central Asia as the next place to suck dry of resources and wealth to power its navy and line the pockets of the rich British merchant class.

Around 1800, the French and Russians secretly made plans for the “Indian March of Paul” — a military expedition against the British Company rule in India. The project was scuttled following the assassination of Emperor Paul I of Russia in March 1801, but the troops that Paul had massed along the Indian border left the British feeling distrustful and more than a bit peevish towards the Russian Empire.

Indeed, Britain started to harbour an almost existential fear that Russia would try to pry India away from them.

Russian expansion was at Britain’s expense

To make matters worse, Russia went to war with the Persian Empire in 1804, seeking to expand its holdings in Central Asia. The war ended in 1813 with with Russia having gained the territory of Georgia as well as the Iranian territories of Dagestan, most of modern-day Azerbaijan, and minor parts of Armenia in Central Asia.

In 1826, Russia again went to war with Persia, this time winning the rest of the Caucuses region. This territorial gain further undermined the position of the British Empire in Persia and marked a new stage in the burgeoning conflict between the two empires.

The “Great Game” between the Russian and British Empires

Russia’s real and threatened territorial gains caused the British to set about trying to sabotage Russian efforts not only in the Indian subcontinent (Southeast Asia), but also in Central Asia.

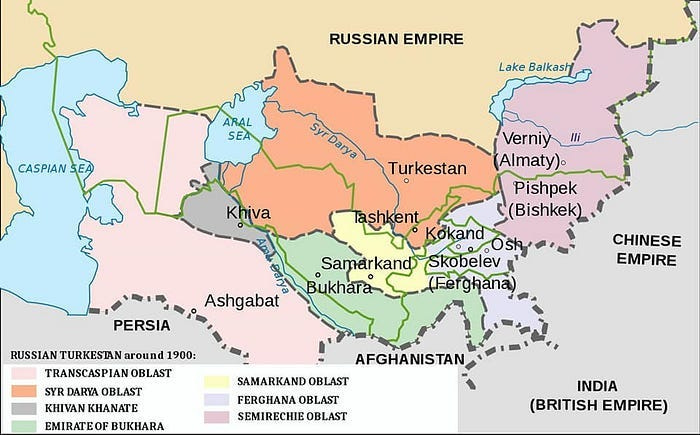

In 1830, Lord Ellenborough, the president of the Board of Control for India, ordered Lord Bentinck, the governor-general of India, to establish a trade route to the Emirate of Bukhara (what is now Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan).

With this move, Britain aimed to create a protectorate in Afghanistan in order to support the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Khiva, and use the “stans” of Bukhara as buffer states against Russian expansion.

This campaign, according to Wikipedia, marked the beginning of what became known as the Great Game. This term, which was was coined in 1840 by a British intelligence officer Captain Arthur Conolly, is used to describe how the two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations to acquire and redefine territories in Central and South Asia.

“The Great Game was an attempt made in the 1830s by the British to impose their view on the world”. — Edward Ingram

The Russians had their own term for this conflict. They called it the Tournament of Shadows, a term reportedly invented by Russian diplomat Karl Nesselrode.

Afghanistan was always key

When we Westerners think of Afghanistan, we mostly think about the Soviet invasion in the 1980’s, or the American invasion in 2001. But for the British, Afghanistan was always a battleground .

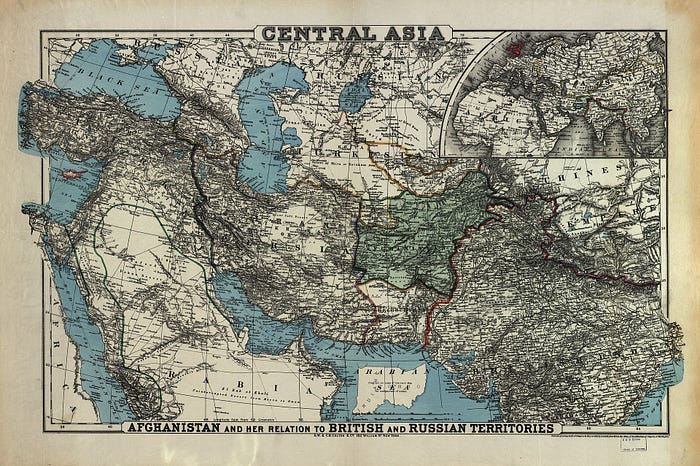

This was because the British always feared an incursion by Russian Empire into their precious Indian holding, and for them it was necessary to have Afghanistan as a buffer or “protectorate” to stave off any Russian encroachment.Map sjowing the strategic

Protecting “The Jewel in the Crown”

India represented Britain’s most prized colonial possession, and needed to be protected at all costs. For this reason, the British fought three “Anglo-Afghan Wars”, from 1838–1842; from 1879–1880; and from 1919–1920. These wars ended up defining the northernmost limit of British expansion in Central Asia, determining the present boundaries of Afghanistan.

The first two Anglo-Afghan Wars were launched by Britain in direct response to “Russian expansionism”, which they felt threatened India. In both cases, the British met with initial success only to be chased out of the country by the local population who mounted a jihad (holy war) on the foreign interlopers.

The Third Anglo-Afghan War took place when Britain tried to take advantage of the Russian civil war that followed the Bolshevik revolution. That war, too, ended in British defeat and Britain was forced to officially recognise the independent and sovereign state of Afghanistan.

Ouch. That had to hurt.

The Crimean War

In the early 1800s, the Ottoman Empire suffered “a number of existential challenges”. Britain’s greatest fear was Russia’s expansion at the expense of the weakening Ottoman Empire. The British thus sought to prop up the Ottomans out of fear that Russia might make advances toward British India or even move toward Western Europe or Scandinavia.

Britain allied with the Ottoman Empire and France in 1854 to fight Russia. The alliance eventually won, forcing the Russians to abandon their Black Sea home base at Sevastopol.

The historian A. J. P. Taylor summed up:

The Crimean war was fought for the sake of Europe rather than for the Eastern question; it was fought against Russia, not in favour of Turkey…. The British fought Russia out of resentment and supposed that her defeat would strengthen the European Balance of Power.

Planned attacks on India

“Just because you’re paranoid, doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you”. That old aphorism applied at the time to the British Empire. In fact, their fears of Russian threats to India were not unfounded. During the Crimean War, there were two separate Russian plans to invade British India and force Britain to divert their forces away from the Black Sea to defend India.

A Great Game rematch in the 20th century

The Great Game had generally quieted down at the end of the 1800’s. In the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, the Russian Empire and British Empire officially ended their rivalry: Russia recognised Afghanistan and southern Iran as part of the British sphere of influence, while Britain recognised Central Asia and northern Iran as part of the Russian sphere of influence.

The founding of MI6

Two years after the Anglo-Russian Convention brought an end to the Great Game, the British intelligence service which was to become MI6 was founded in 1909 as the Secret Service Bureau (SSB).

Then. the Bolshevik Revolution gave Britain a new opportunity to attack Russian interests. The Great Game was on again, but instead of Imperial Russia as the great enemy, it was Communist Russia.

Leveraging the Russian Civil War

The civil war that followed the revolution, which pitted the “White Russians” against the “Red Russians” led Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for War, to say in 1919:

“The aid which we can give to those Russian armies which are now engaged in fighting against the foul baboonery of Bolshevism can be given by arms, munitions, equipment, and by the technical services”.

Sounds like what we are doing for Ukraine, doesn’t it?

Britain invested heavily in helping thwe White Russians defeat the Bolsheviks, but in the end, the Red Army prevailed. It was then that the British turned once more to the “shadow” war of the Great Game.

The real “James Bond”

Under Churchill’s aegis, the SSB evolved into the modern Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6. It was at this time that the British spooks deployed a formidable asset to Russia, a man known as “The Ace of Spies” named Sidney George Reilly, an Odessa-born Ukrainian who infiltrated the Soviet government, tasked with the destruction of the Bolshevik regime.

Reilly operated for years inside the USSR, even fomenting an abortive coup d’état against Lenin. He was eventually discovered, arrested and executed by the Soviets in 1925, but not before becoming a legend in his own right. It is even believed that Reilly formed the inspiration for Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

WWII and “Operation Unthinkable”

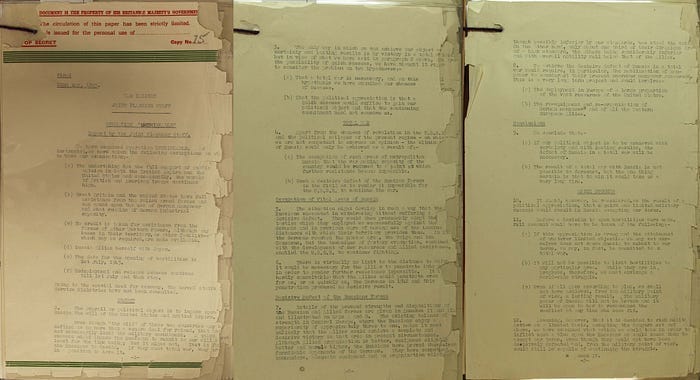

The end of WWII brought Churchill another chance to destroy Russia. He led the Western Allies in hatching a plan called Operation Unthinkable, designed to conquer and occupy the war-torn and weakened Soviet Union, with a stated objective that echoes Edward Ingram’s characterisation of the Great Game:

“The overall or political object is to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and British Empire” — Operation Unthinkable (1945)

The operation was planned by the Joint Planning Staff and presented to Winston Churchill in May, 1945. The proposed launch date of the operation was July 1, 1945.

Operation Unthinkable’s potential success, according to the planners, depended on enlisting the Russian-hating Poles as well as “the re-equipment and re-organisation of German manpower” (i.e., NAZIS):

“Great Britain and the United States [will] have full assistance from the Polish armed forces and can count upon the use of German manpower and what remains of German industrial capacity”.

The planning brief concludes that in order to achieve the objective, “the defeat of Russia in a total war will be necessary”.

In short, this was Churchill’s plan for World War Three, and it ended with the complete defeat and “Occupation of Vital Areas of Russia”.

Needless to say, Operation Unthinkable was never implemented. But the great western dream of conquering Russia has always remained — and still informs and shapes western policy towards Russia.

The end of the Raj and Britain’s loss of India

In 1947, the British Raj in India was home by two nationalist movements: one movement called for the creation of India, India, a pluralist democracy. The other called for creeating Pakistan, a homeland for the Muslims of South Asia

The United Kingdom, militarily and economically exhausted by World War II and beset by the anti-colonial movements that had begun to challenge empires, agreed to independence and partitioning of the sub-continent.

Britain thus withdrew, and gave up its Indian colony, the jewel of its colonial crown, under the terms of the Indian Independence Act.

With India no longer part of Britain, one would think that the UK’s Great Game with Russia might have come to a close.

It did not.

The Cold War — that never ended

Following the end of WWII, the newly formed CIA partnered with MI6 to launch various operations, including Operation GLADIO, which relied on unreconstructed Nazis and various Fascists to carry on their fight against the Soviets.

The Great Game was entering yet another phase, a “Spy versus Spy” game of espionage, assassination, sabotage, coups, election rigging, economic warfare, propaganda, and proxy wars — anything short of open war between the East and the West.

That Cold War continues to this day.

The US and its western allies, and particularly CIA and MI6, continue to wage a Great Game like contest with Russia.

The Second Great Game

Just look at Afghanistan. Central Asia continues to be an area of competition and conflict, with the United States and United Kingdom backing Mujahideen in the 1980’s to “weaken” and “bleed” Russia, giving the Russians “their own Vietnam”.

The Afghan conflict is what Dr Geraint Hughes, a Diplomatic and Military Historian at King’s College London, calls The Second Great Game:

The Soviet intervention in Afghanistan was condemned not only by the Western powers but also by non-aligned states as an act of imperialist aggression, and fuelled contemporary fears that the USSR was pursuing an expansionist policy that threatened world peace.

The British and the Americans carried on the fight against Russian expansionism by transforming Pakistan into what it was always meant to be: a militarised bulwark against Russian expansion. Indeed, in the Soviet-Afghan War, it was the powerful Pakistani dictator General Zia-ul-Haq who fought the Russians on behalf of the Anglo-Saxon West. General Zia, who had been trained both by the British and the American militaries, used his vaunted Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to run the proxy war next door and also facilitate the US’s arming of the Mujahideen.

The defeat of the Russians in Afganistan triggered the dissolution of the USSR, which finally collapsed in 1991. Again, one might have thought that the Great Game playing of the Cold War could finally stop.

It did not.

“Poking the Bear”

The Cold War did not end with the West’s “victory” over Communism — the fall of the USSR only ushered in a new inning in the Great Game. The British and their “colonial cousins” in the USA immediately returned to the old habits of espionage and provocation aimed at Russia (“poking the bear”).

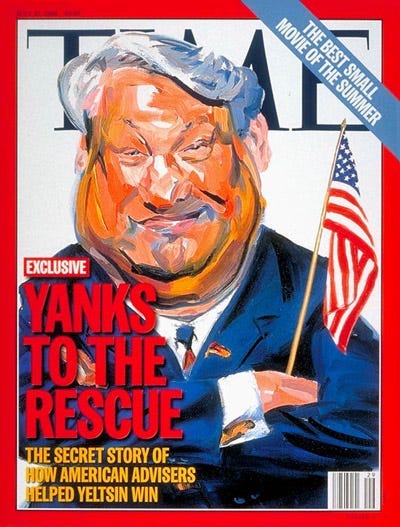

The expansion of NATO, the stationing of missile batteries in Eastern Europe, the direct interference in Russian elections — these were all new techniques to try and destroy the great Russian state, so it could be broken up into easily “manageable” factions that Western financial and economic interests could easily control — and exploit.

Ukraine is just one more move in the Great Game

In 1997, Zbigniew Brzezinski, who had served as Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, published a book entitled The Grand Chessboard. In it, Brzezinski presents Ukraine as the pivotal country for containing Russia, declaring that:

“Ukraine is the critical state, insofar as Russia’s future evolution is concerned. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.”

Thus the goal of US foreign policy for the past decades has been to “pry” Ukraine away from Russia.

2004: The Orange Revolution

In 2004, the CIA engineered one of its patented color revolutions in Ukraine. The so-called “Orange Revolution” sought to overthrow Russian-friendly government leaders and install a more U.S.-friendly regime.

William Schneider, writing in The Atlantic at the time, described how the Orange Revolution exposed the divisions in Ukraine:

Ukraine’s east is mostly Russian-speaking, Orthodox in religion, and strongly pro-Russian. Most people in Ukraine’s west speak Ukrainian and adhere to a church that acknowledges the authority of the Roman Catholic pope. Western Ukrainians are intensely nationalistic and distrustful of Russia.

The Orange Revolution failed when the pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovich won the election runoff. But that didn’t stop the US …

2014: The Maidan Coup

The Western goal in Ukraine finally came within reach when the US supported the Maidan Coup in 2014 and installed a pro-Western, pro-US, pro-NATO, pro-EU government that was hand picked by the US State Department.

Arseniy Yatsenyuk, the interim Prime Minister that the US put in office, was a Pro-Nazi revisionist, racist and ardent Russia hater who promised his government would “cleanse sub-humans” from Eastern Ukraine. They even published his Nazi plan for ethnic cleansing on the Ukrainian US Embassy web site (the text has since been redacted to substitute “inhumans” (not a real word) for the original “subhumans”, but the point is unmistakable.

2024: The CIA is still working behind the scenes

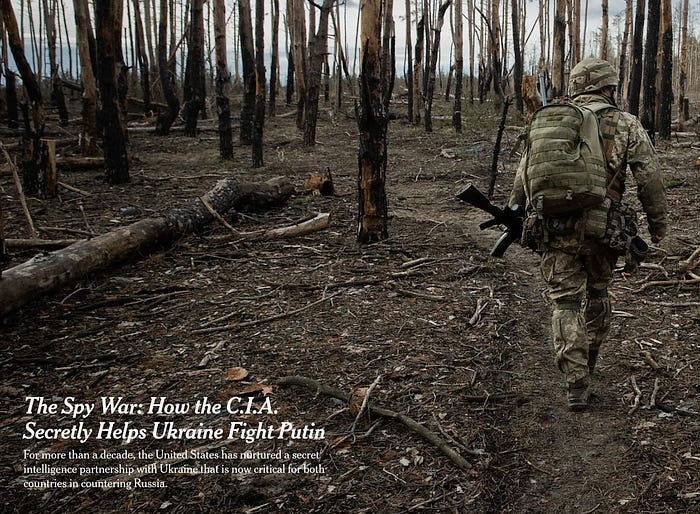

A recent New York Times article, entitled: “The Spy War: How the C.I.A. Secretly Helps Ukraine Fight Putin”, details how the Great Game was being played out in Ukraine over the past decade or longer.

It took root a decade ago, coming together in fits and starts under three very different U.S. presidents, pushed forward by key individuals who often took daring risks. It has transformed Ukraine, whose intelligence agencies were long seen as thoroughly compromised by Russia, into one of Washington’s most important intelligence partners against the Kremlin today.

The article goes on to describe the CIA’s “network of spy bases constructed in the past eight years that includes 12 secret locations along the Russian border”. It also tells how CIA “helped train a new generation of Ukrainian spies who operated inside Russia, across Europe, and in Cuba and other places where the Russians have a large presence”.

In short, Ukraine has become one of the US’s most important chess pieces in this latest iteration of the Great Game.

#End.

If you liked this post, please consider leaving me a tip! Donations support my independent, ad-free writing.

===========================================================================

Awesome article! We must not forget history and this was a terrific recap of important conflicts that affect us today!!